Donors

Henrietta Alexander, Eide Bailly, Daniel Berger, David Bird, Karen Brender, Roy Britton, Veronica Brice, Steve Bly, Linda Behrman, William Brock, Spencer Beebe,

George Cawthon, CC, Eide Cleaveland, Kathy Coontz, Bob Collins, Conoco Phillips, J. Colvin, Jeff Cielk, Donna Daniels, Disney Worldwide Service, Walt Disney

Animal Kingdom, Mary Ann Edson, Phil Eldredge, Jan Erhart, Bob Fitzsimmons, Nancy Freutel, Peter Harrity, Larry Hays, Herrick Investments, Higgins & Rutledge

Insurance, David Horwath, Wally Imfeld, Bryan Jennings, Robert W. Johnson IV Charitable Trust, Louise Kelly, Judith King, Luther King Capital Management, Eileen

Leisk, Bill Mattox, Mimi McMillen, Ray Mendez, Microwave Telemetry Inc., Don Moser, MTI, Rishad Naoroji, Tyler Nelson, North American Grouse Partnership, Bob

Oakleaf, E. Owens, Pioneer Hi-bred International, Timothy Pirrung, Garrett Riley, Patricia Rossi, Leonardo Salas, Cynthia Salley, William Satterfield, Jacqueline

Schafer, Margaret Schiff, Linda Schueck, Peter Simon, Richard Snyder, Sue Sontag, Jim Tate, Terence Tiernan, Linda Thorstrom, Skip Tubbs, Wayne Upton, US Bank,

Veco Polar Field Services, William Wade, Richard Watson, Conni Williams, E. Williams, George Williams, Margaret Wood, William Wood, Jesse Woody, Mike & Karen

Yates

W

illiam A. Burnham, our President and

leader for the past 23 years, has died

at the age of 59 after a brief battle

with cancer. What can one say about a person who dies

before his time? In Bill’s case quite a lot.

We all die; “therefore,” as John Donne cautioned,

“never send to know for whom the bell tolls; it tolls for

thee.” How long we live is not as important as how well

we live—how much we contribute to the good of

humanity and to the welfare of the earth, the sustainer

of all life. Bill Burnham made outstanding contributions

to the preservation of his beloved birds of prey and

other wildlife, and to nurturing the habitats they require.

Therefore, we should not mourn but celebrate his life

and move forward, strengthened by our association with

him and thankful for all he has done.

Bill became associated with The Peregrine Fund

(TPF) in 1974, after receiving his MS degree at Brigham

Young University under Prof. Clayton White. That sum-

mer, Jim Weaver met him on a field trip to western

Greenland. Hiking and camping with Bill in the arctic

wilderness, Jim became greatly impressed by his stamina

in the field and by his eagerness to face up to hard chal-

lenges. Jim recommended that TPF hire Bill to head up a

new program of captive breeding and reintroduction of

Peregrines that we were just starting in collaboration

with the Colorado Division of Wildlife to restore falcons

in the Rocky Mountains.

On Christmas eve of 1974, Bill and his wife, Pat—

soon to be joined by a son, Kurt—moved into some

rooms on the second floor of an old game farm facility

the Colorado Division of Wildlife made available for

TPF use on the outskirts of Fort Collins. Kurt was born

in May, 1975 at the same time the first baby Peregrines

were hatching. Pat not only mothered her child, she also

cared for many young falcons over the years and always

remained the person Bill relied on most for running The

Peregrine Fund. Bill quickly attracted several skilled and

dedicated associates to help with the breeding and

release of Peregrines. Two of them, Bill Heinrich and Cal

Sandfort, are still with TPF 31 years later.

By the 1980s the Fort Collins team, under Bill’s

supervision, had produced hundreds of Peregrines and

had released them in several Rocky Mountain states and

in the Pacific Northwest. At the same time all this inten-

sive work was underway, Bill somehow managed to earn

a Ph.D. degree from Colorado State University without

ever taking time off from his job. Bill’s effectiveness in

managing the western operations did not go unnoticed

by the fledgling board of directors of TPF. In 1977 he

was elected to the board of directors, and in 1982 he

became the fifth “Founding Member” of the board, join-

ing Bob Berry, Frank Bond, Tom Cade, and Jim Weaver.

When TPF had an oppor-

tunity in 1983 to consolidate

its eastern program at Cor-

nell University and its west-

ern operations into one

facility, Bill was put in charge

of finding a location, con-

structing the new campus,

and making the move. At the

same time the directors

decided to expand the mis-

sion of The Peregrine Fund to embrace work on birds of

prey worldwide. Through Bill’s leadership and ability to

organize the volunteer efforts of many falconers and rap-

tor enthusiasts, members of the business community,

and government agencies into a unified and productive

endeavor, the World Center for Birds of Prey came into

existence on a hillside overlooking Boise, Idaho, in

1984. The site was dedicated in May, construction began

soon after with much comradeship and enthusiasm, and

the birds from Fort Collins were in their new quarters

before the next breeding season in 1985. The Cornell

birds followed a year later.

It quickly became clear to the small group of directors

that TPF’s expanded global mission would require a much

bigger board of influential people and a strong and deter-

mined chief executive. Bill became President in 1986, and

he began to build a more active and diverse board of

directors, including people from the business world, sci-

entists, and conservationists. Through Morley Nelson’s

introductions, he began to establish personal relation-

ships with local business people in the Boise community,

meeting weekly with some of them for breakfast and dis-

cussion. Several joined the board and brought some of

their friends along. Our vice presidents, Jeff Cilek and

Peter Jenny, whom Bill wisely chose to help him, made

important additional contacts, as did Frank Bond and Bob

Berry. Currently the board consists of more than 30 mem-

bers, and it is considered to be one of the strongest boards

of a non-profit, conservation organization in the country,

thanks largely to Bill’s ability to forge personal ties with

influential and supportive people.

The combined fund-raising abilities of Burnham,

Cilek, and Jenny, and their equal facility in dealing with

government bureaucrats and legislators, were beautiful

to observe in action. They allowed TPF to move beyond

its original focus on the Peregrine and to take on many

other projects around the world, although we had been

involved previously in cooperating with Carl Jones on

restoration of the Mauritius Kestrel.

The first major effort was the “Maya Project,” which

grew out of Pete’s and Bill’s interest in the Orange-

Tom J. Cade

1

Thank You, Bill

(1947–2006)

Ben Widener

(continued on page 2)

…he wisely left

us with the

capability to

move forward

without him,

but ever in

memory of

him.

with The Explorers Club’s Lowell Thomas Award in 2004. In

2006 he was chosen to receive the Conservation Medal of the

Zoological Society of San Diego in recognition of his many con-

tributions to the conservation of birds of prey.

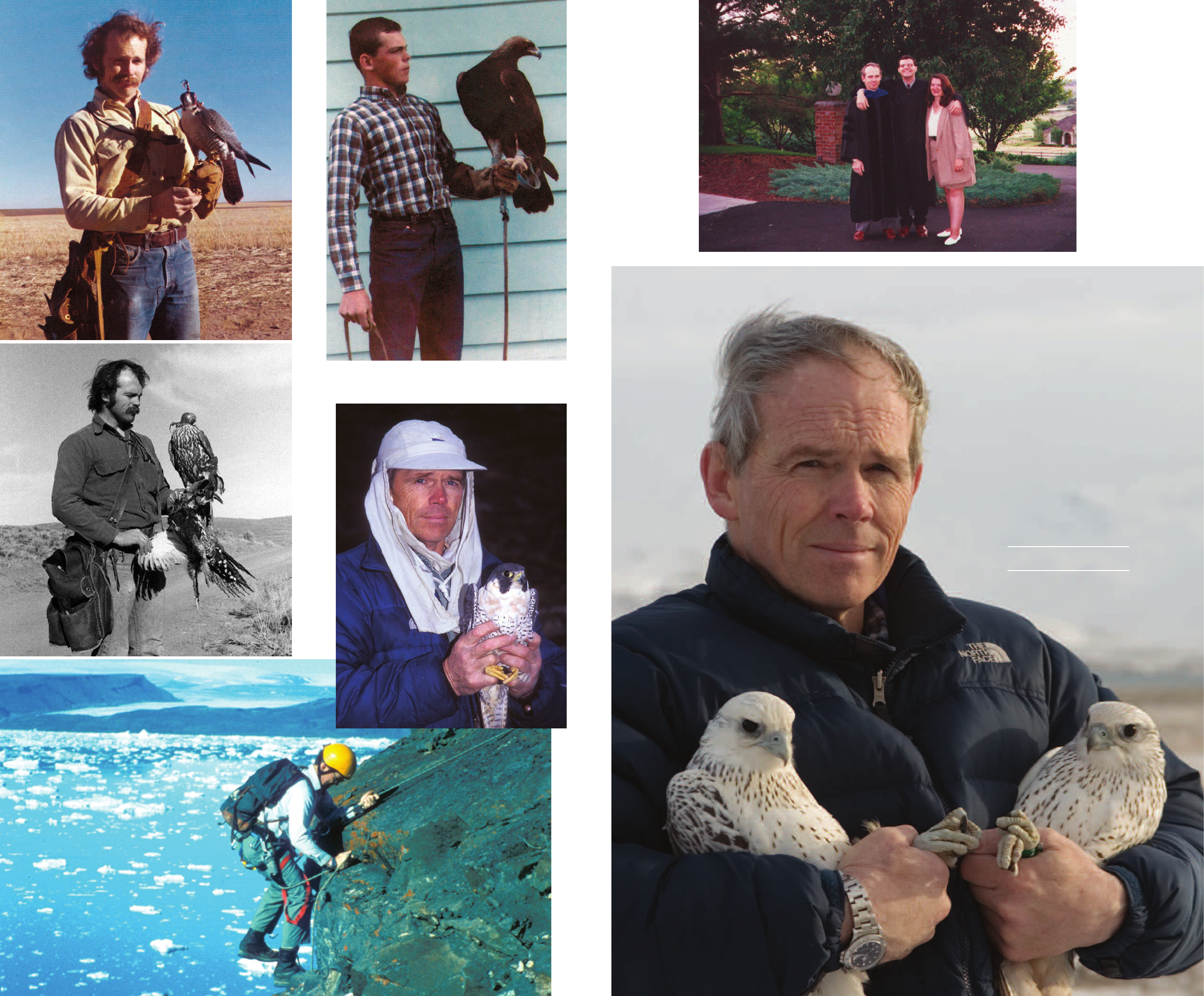

I knew Bill for 32 years and watched in admiration how he

developed as a person and crafted The Peregrine Fund into an

outstanding organization. Bill was the quintessential workaholic,

an early riser, often in his office before 6 a.m. and putting in

many seven-day weeks. He was a natural-born leader, attracting

many good and loyal people to work with him. He viewed his

position as President to be one of making the big, strategic deci-

sions, and he left his associates free to handle most of the tacti-

cal, day-to-day things. Consequently, he empowered a strong,

well-organized group of people to carry on after him.

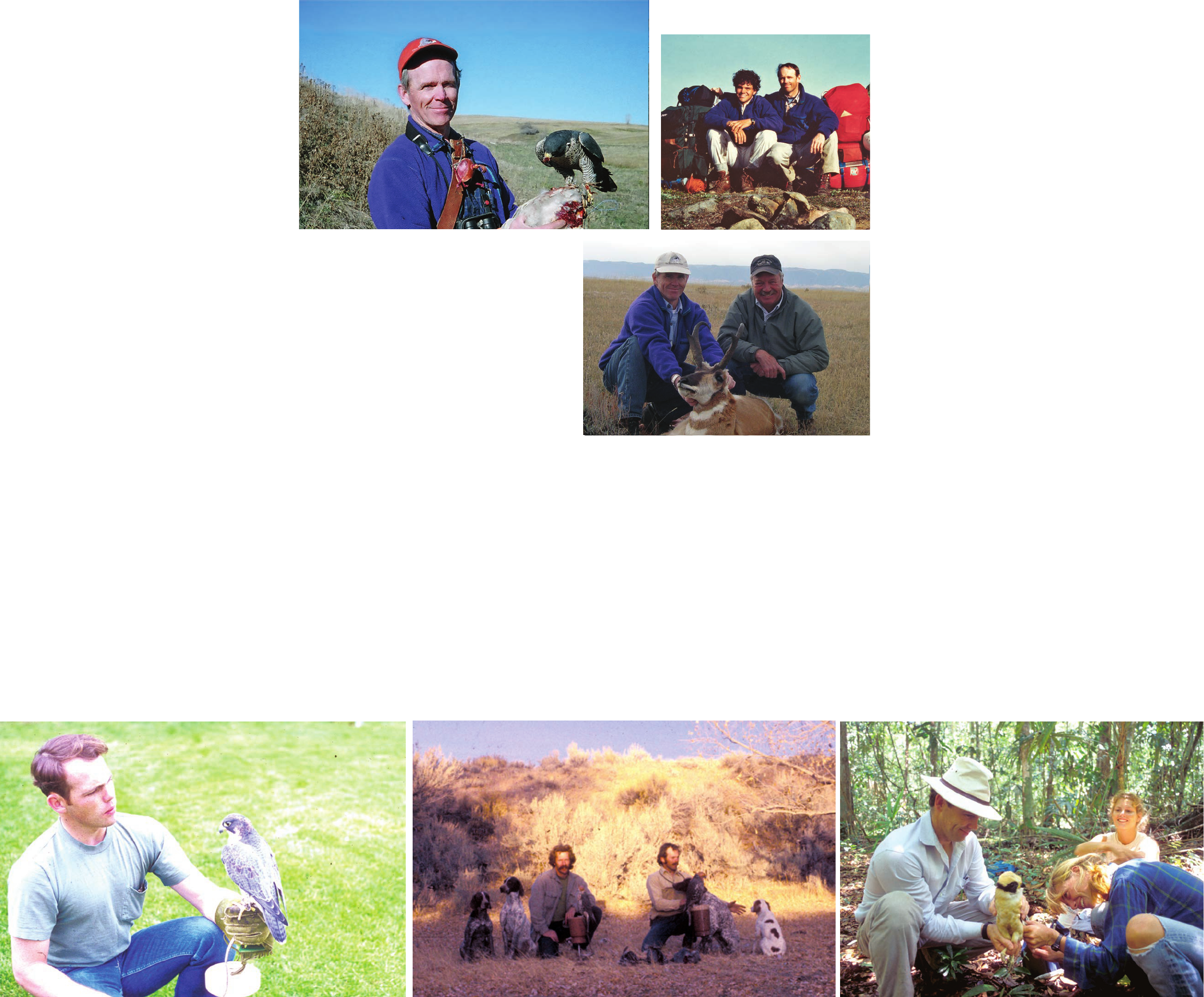

Bill worked hard, but he also played hard. He was not a large

man, but he had great body strength and great endurance. His stam-

ina in hiking and backpacking was legendary. On hikes in Green-

land looking for falcon eyries, he was always ahead and would be

set up in camp brewing coffee by the time the rest of us straggled in.

Danger excited and challenged him. He actually enjoyed rap-

pelling on a rope hundreds of feet down cliffs to enter falcon

eyries. You can read his account of one such climb on a karst cliff

in Guatemala in search of the nest of the Orange-breasted Falcon

(page 189 in his book A Fascination with Falcons, 1997). Once in a

campfire discussion, we both agreed that one of the things that

makes true wilderness so exciting is the possibility of being eaten

by a grizzly bear. Remove the bear—no more wilderness.

Bill was an avid falconer, especially in his earlier years. When

he became President of TPF he selflessly reduced his practice of

falconry, a time-consuming avocation, so that he could devote

more attention to the needs of the organization. He did continue

to hunt big game seasonally, often with his close friend, Pete

Widener, and more recently, upland game birds with Kurt and

other companions. I know it was one of his great joys to return to

falconry in recent years.

Although Bill had the reputation of being a practical, rough-

and-ready, can-do, let’s-get-it-done-now, sort of guy, he also

revealed a more philosophical and meditative—even poetic—side

to his character from time to time. Some of his reflections on the

need for conservation and the value of wild animals and wild

places in his book, A Fascination with Falcons, reflect a deep devo-

tion to nature. I especially like his short essay on “The Scent of a

Peregrine” published in Return of the Peregrine (2003, p. 222), a

book he conceived and helped edit: “There is nothing in the world

that smells like a newly captured Peregrine. She smells like a mix of

willow and birch of a green arctic tundra, the scent of pine as the

rays of the sun pierce the forest to dry the needles of the morning

dew, the freshness of the golden prairie grass on an autumn day,

and the fragrance of the sea breeze through marsh flowers.”

Bill loved to explore new places and to test his endurance

against hardships. One of my strong memories of him is how he

stood stalwart and confident at the controls of our “Safe Boat”

with Kurt by his side, as we faced into a gale and icy rain, while

traveling up the west coast of Greenland with icebergs passing to

port and starboard. Jack Stephens and I crouched in the back of

the open boat, huddled in our rain parkas trying to keep from

freezing to death, while Bill and Kurt faced the brunt of the storm

during hours of hard travel to reach a safe harbor.

When traveling under such conditions, I tend to enter a kind

of sleepy lethargy, and all sorts of random thoughts and images

drift through my groggy consciousness. Once I glanced up and

saw Bill still at the wheel, and some words from history came to

mind: “There stands Jackson like a stonewall.” I then realized

that our “Safe Boat,” said to be unsinkable, was safe not so much

because of its design as because of who was at the helm.

One of Bill’s legacies is that he has left behind a strong and

capable wife and son who have guided us with grace and dignity

through these last days with Bill. He has also left behind a dedi-

cated and active group of colleagues, which he molded into an

internationally respected conservation organization—The Pere-

grine Fund—and which he wisely left with the capability to move

forward without him, but ever in memory of him.

3

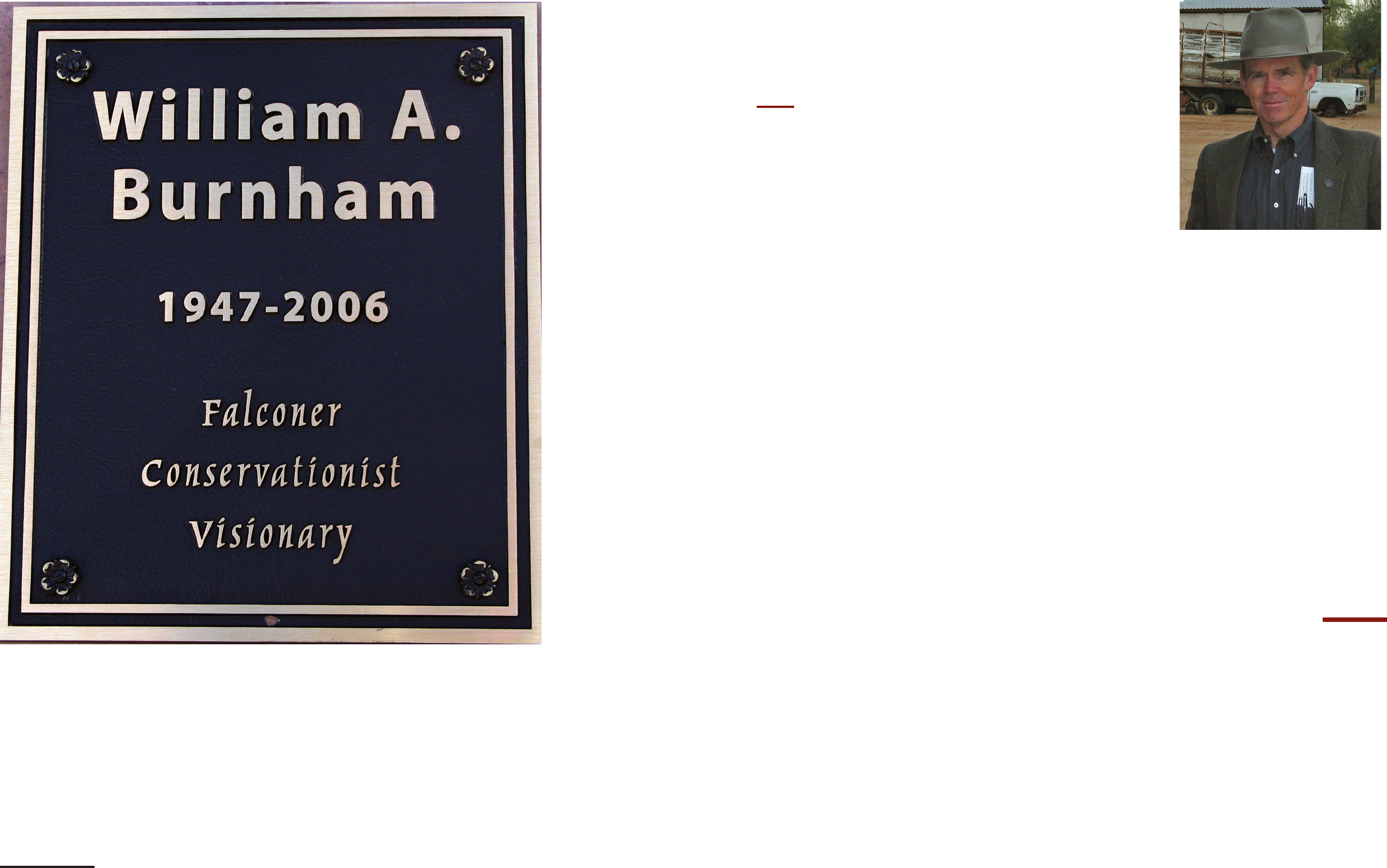

Clockwise, Bill duck hawking with his female Peregrine Falcon,

Ebony, near Sheridan, Wyoming, in 2004; with his son Kurt con-

ducting Peregrine Falcon surveys near Kangerlussuaq, Greenland,

in the summer of 1992; and with his best friend Pete Widener

antelope hunting near Buffalo, Wyoming, in the fall of 2005.

All gifts received in memory of Bill will be placed equally in the

general endowment for The Peregrine Fund and the endowment

for The Archives of Falconry.

File photoKurt K. Burnham

Lucy Widener

breasted Falcon, a rare species of the Neotropics. Located in Tikal

National Park, Guatemala, the fieldwork for the Maya Project was

headed up by Dave Whitacre with several assistants, notably Rus-

sell Thorstrom, and included local Guatemalans. Carried out over

several years, the project resulted in new scientific descriptions of

the life histories of more than 20 species of tropical raptors and a

detailed analysis of their community ecology, as well as studies

on Neotropical migrants and the training of a number of

Guatemalan biologists.

In 1990, a comparable project started up in Madagascar and

continues to the present, under the supervision of Rick Watson,

again with impressive fieldwork by Russell Thorstrom. It has

focused on the ecology of the rare and endangered raptors found

only on the island, notably on the Madagascar Fish Eagle.

The list of overseas projects quickly expanded under Rick’s

supervision as International Programs Director, including activi-

ties in Africa, New Guinea, Mongolia, Pakistan and India, and

Latin America. In Hawaii Bill set up a program for the captive

breeding and reintroduction of endangered bird species unique

to the islands and oversaw the development of two breeding

facilities. Under the management of Alan Lieberman and Cyndi

Kuehler, this program was later transferred to the Zoological Soci-

ety of San Diego. Bill also established a new branch of The Pere-

grine Fund located in Panama City—Fondo Peregrino-Panama,

and supervised the construction of the Neotropical Raptor Center

to carry out research and conservation involving raptors of Latin

America and the Caribbean, again emphasizing rare, little-known,

and endangered species, such as the Harpy Eagle, Orange-

breasted Falcon, and Ridgway’s Hawk.

One of the most important but least heralded accomplish-

ments spearheaded by Bill was the discovery of the cause for the

“Asian Vulture Crisis”—the virtual extinction of three species of

griffon vultures on the Indian Subcontinent in just the past

decade. In collaboration with a former associate of TPF, Lindsay

Oaks, now a veterinarian specializing in avian virology at Wash-

ington State University, TPF biologists obtained conclusive proof

that a veterinary drug called diclofenac was fatal to vultures that

fed on carcasses contaminated with this chemical, which had

become widely used on the Subcontinent as an analgesic and

anti-inflammatory for domestic livestock. In 2006, as a direct

result of this discovery, the governments of India, Nepal, and

Pakistan banned the use of diclofenac for veterinary purposes.

This achievement is in many ways equivalent in importance to

the banning of DDT in the United States in 1972. Recovery of the

vultures is now a possibility.

The study of Peregrines and Gyrfalcons in Greenland was Bill

Burnham’s favorite project. His first trip to Greenland was in 1972

when Bill Mattox started the Greenland Peregrine Survey, which

on Mattox’s retirement in 1998 he transferred to TPF. Burnham

expanded the project to include Gyrfalcons and the prey species

falcons eat, and with help from his son, Kurt, established the

“High Arctic Institute” at Thule, using a decommissioned facility

leased from the U.S. Air Force. Father and son worked together in

Greenland each summer for the past 16 years, along with many

other associates. Bill was able to fulfill his last wish by making two

trips to Greenland in the summer of 2006, despite an incapacitat-

ing illness that would have kept anyone else in hospital.

Since the removal of the Peregrine from the list of endangered

species in 1999, an accomplishment that involved Bill and other

TPF staff in negotiations with the federal government for more

than five years, our two main domestic projects have been the use

of captive breeding and reintroduction to restore nesting popula-

tions of Aplomado Falcons in the Southwest and California Con-

dors in northern Arizona. By negotiating use of the “safe harbor”

policy for private landowners in Texas and the non-essential

experimental population designation under section 10(j) of the

Endangered Species Act for condors in Arizona and falcons in

New Mexico, Bill quietly but effectively maneuvered TPF through

a tangle of political and societal issues that initially impeded the

development of these projects.

Believing strongly that public education and academic train-

ing are the keys to successful conservation, Bill promoted projects

such as the Velma Morrison Interpretive Center, which welcomes

thousands of visitors each year, and the Gerald D. and Kathryn S.

Herrick Collections Building. The latter houses a major ornitho-

logical library, egg and specimen collection, and the Archives of

Falconry. Both facilities attest to Bill’s commitment to education,

as does TPF’s support over the years of more than 20 Doctoral

degrees, 53 Master’s degrees, and numerous Bachelor degrees and

high school diplomas earned by students around the world.

Bill also participated in many activities external from but

related to TPF interests. For example, he helped establish a unique

graduate program in raptor biology at Boise State University

(BSU) and became an adjunct professor in the program, supervis-

ing a number of students who carried out research associated with

TPF projects. Secretary of the Interior Emanuel Lujan appointed

Bill to the National Public Lands Advisory Council; he also served

as a trustee on the BSU Foundation; as a conflict mediator and

then member of the Bureau of Land Management’s Oversight

Committee for the Snake River Birds of Prey Area; on the council

for the multi-agency and university Raptor Research and Technical

Assistance Center at BSU; on the board of the North American

Raptor Breeders’ Association; on the advisory board of the Walt

Disney Company’s Animal Kingdom; as an adviser to the Philip-

pine government on science and conservation for the Philippine

Eagle; as a board member of the Philippine Eagle Foundation, Inc;

and in various other similar capacities.

He was elected to be a “Fellow” of the Arctic Institute of

North America and of The Explorers Club. He was also presented

2

Thank You, Bill (continued from page 1)

Even at age 14, Bill’s rock climbing skills were evident and

developed to the point where he could pull an eyess eagle

THE PEREGRINE FUND

THE PEREGRINE FUND

working

to conserve

birds of prey

in nature

fall /winter 2006

newsletter number 37